Restitution for Salvation

While salvation was impossible for usurers in the early middle ages, the Gregorian Reform of the twelfth century introduced the concept of Purgatory and gave usurers hope of salvation through restitution. One could not stay in Purgatory forever and would be able to make his presence there shorter or completely unnecessary by paying back for all of his sins or having someone do it for him after his death. As a result, many bankers, including the members of the Medici family, mentioned the restitution of usurious profit in their wills.

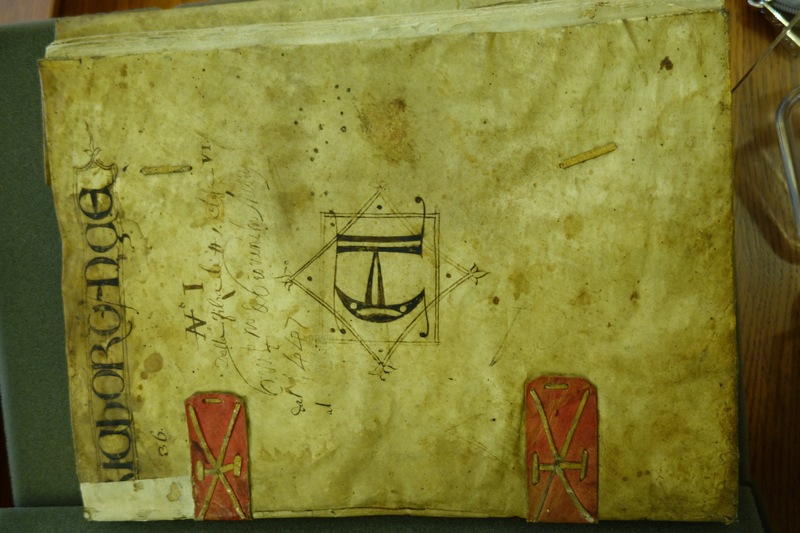

One example of that comes from a private book of memoranda that is kept in the Baker Library at Harvard Business School. One of over 170 account books left by the Giovenco branch of the Medici family, which is not as well known as the Salvestro branch that later seized political control over Florence, this account book belonged to Giuliano di Giovenco de’ Medici and his son Francesco di Giuliano. There, Francesco lists a number of restitutions that he made to whomever he and his father have ever lent money with interest.

Such a simple solution to the problem raises a question: if you can just save your soul and that of your father by just repaying money to your all former clients, why commission art to restitute for usury? As I said before, the Giovenco branch of the Medici family is not very well-known because it was not involved with the Medici bank, and engaged in trade much more than in banking. Inside a thick volume of accounts and personal memories, only a few pages were dedicated to the Giuliano’s and Francesco’s banking activity, and only two to the restitution for it.

This means that hardly a very large percent of the father and son’s income came from banking, and giving it back to clients would not have impoverished the family. But what if you are a full-time banker and all of your life’s income came from what was considered to be usury and illicit profit?

Given the ambiguous definition of usury, the varying regulations regarding how much interest could be legally charged without being considered usurious, and the simple unreliability of bankers’ personal records on how much of their gains were usurious, it must have been almost impossible for the bankers and their posterity to determine the exact amount of money that had to be restituted to the people from whom that interest had been extracted. Moreover, what was to be done with all the ill-gotten money that had been spent, lost, or invested in real estate? Was everything that the banker had purchased with his usurious money to be sold and given back to the world, thus leaving the banker’s children penniless?

Given all these complications, the practice of bankers’ wills specifying that their heirs make restitution for ill-gotten gains, was far from universal in the thirteenth-century, and became even less common by mid-fourteenth century. To make the process easier, local clergy in different parts of Italy started coming up with specific guidelines regarding the restitution of usury.

For instance, in early fourteenth-century Padua, a document inserted into episcopal formularies called the Method of Restituting Security Interest of Some Dead suggests that, with the bishop’s approval, restitution of merely part of the ill-gotten gains would be sufficient to save the usurer’s soul. Because it was difficult to know exactly how much needed to be restored, it was up to the usurer’s confessor to decide upon the terms of restitution and to determine whether the usurer had met those terms.